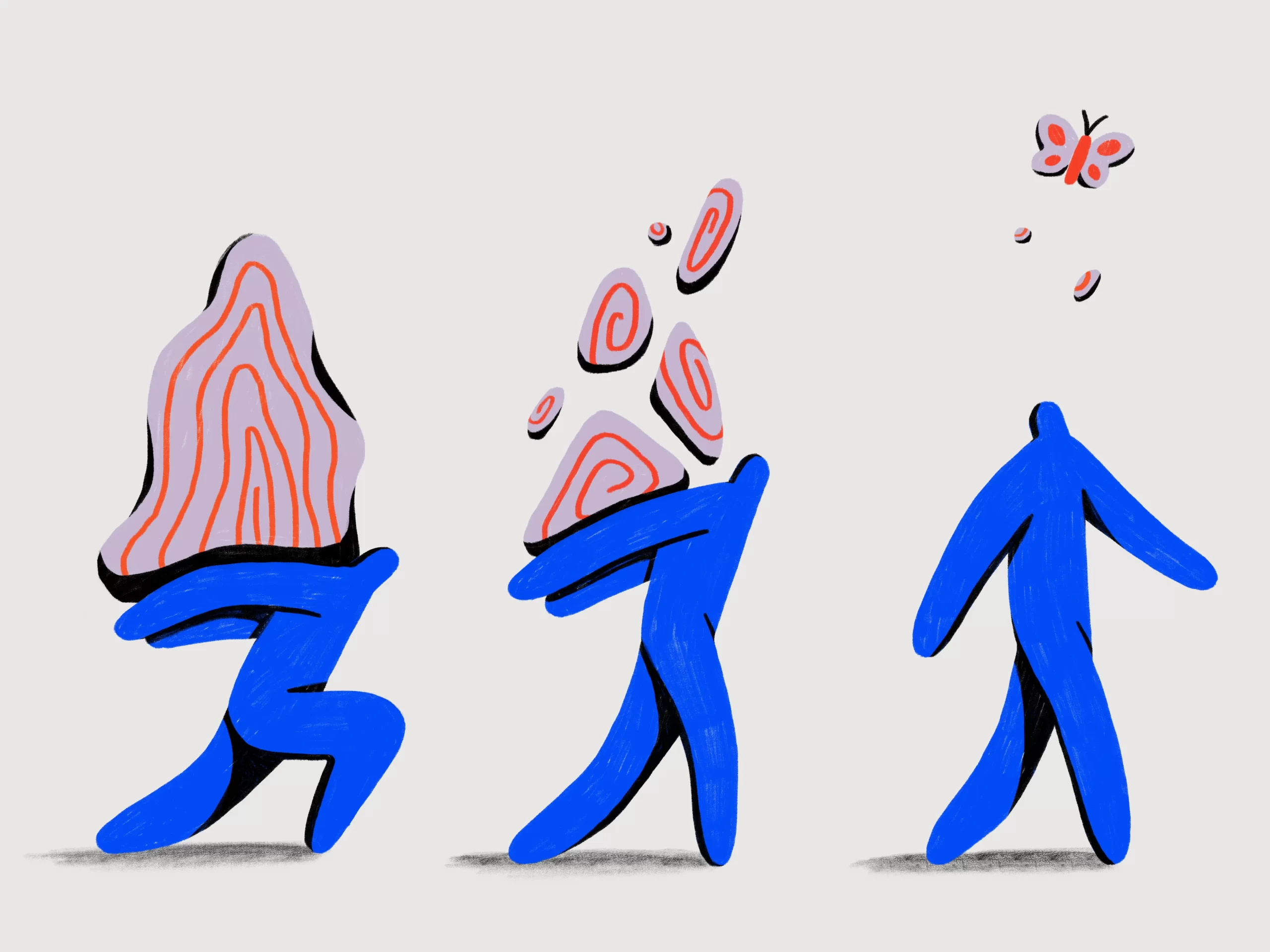

The transmission of trauma, also known as ‘intergenerational trauma,’ is the passing down to younger generations of the oppressive or traumatic effects of a historical event.

It frequently occurs between parents and children. Sometimes a mother conveys her own traumas to her child, and the child lives in isolation and thus becomes a victim.

It is also possible that a person is born with it as a result of what happened to the mother prior to the birth of the child.

It is difficult to discuss trauma without mentioning the 1994 Tutsi Genocide, which killed over a million people and caused a great deal of trauma that was passed down from generation to generation.

It is a problem seen among young people, particularly among children whose parents survived the Tutsi Genocide. The extreme trauma and other mental health problems that the parents experienced had a direct impact on the children they raised.

It is common for a child to be mistreated without knowing why, because they do not know what kind of trauma their parents experienced or what kind of healing they require.

Sometimes parents prefer not to burden their children with their trauma and instead keep it to themselves, but this has an impact on the children as well.

Because of the severity of the Genocide, even though the mother avoids telling her child and chooses to bear the burden on her own, on the other hand, it causes her to live in that confusion, which can have a negative impact on her mind.

The transmission of trauma is not only caused by genocide; it can also be caused by other events in the person’s life, such as abuse, violence, and poverty, among other things.

Psychologist Dr Ndagijimana Jean Pierre, says that apart from the parents but the children who also saw the Genocide-and are the youth of today-have their own traumas they are dealing with.

“It’s traumatic for an adult to experience such a thing; imagine what a child can go through,” he said, “So that’s the generation we have now. And the intergenerational trauma is not really surprising.”

He goes on to say that this trauma has crucial significance in explaining the life young people are living today.

A cure: Learning from history

Dr. Ndagijimana explains that what happened to Rwandan society should be used to break the trauma by raising resilient youth because they are the ones who will lead this country.

“Parents should not transmit their traumas to their children; instead, they should use their experience to teach lessons,” he said, “They should demonstrate the cause as well as methods for dealing with and preventing it.”

He goes on to say that learning from history has brought people comfort because they would not have been able to make peace with it otherwise.

According to Gatabazi Clever of the Never Again Rwanda group, there is a shared (transmission trauma) and cross-generational trauma (Intergenerational trauma).

He claims that this often crosses centuries, and that in Rwanda, it tends to come from Genocide survivors, Genocide perpetrators, Genocide victims, and Genocide survivors who don’t know their origins; they all transmit their trauma to their children because it is part of their daily lives.

According to him, this problem can only be solved through the collaboration of various sectors such as the government, the public and private sectors, and other organizations and institutions that will work together to solve the problems.

He explains that because this problem is prevalent among young people, they decided to start with families. They formed various groups where young people could meet and discuss their various problems in order to try to heal together.

“We also have what we call ‘Youth Lab,’ a program that connects parents and young people to discuss these wounds, which is accompanied by discussions called ‘inter-generational dialogue,’ aimed at connecting parents and young people so that trauma transmission is completely broken,” he said.

Never Again Rwanda currently has 90 groups in the districts of Gasabo, Nyagatare, Rutsiro, and Musanze, with a total of 2090 people, including elders and youth.

Nzabonimpa Emmanuel, a researcher at Community Based Socio-Therapy: CBS, says that their Mvura Nkuvure program, in combating this problem, focuses on those who were present during the genocide to help them.

Later, they learned from the parents that this problem exists in young people as well and that they, too, require assistance.

He explains that one of the causes of this trauma among children is parents who refuse to tell their children about their experiences during the Tutsi Genocide.

“It allows children to deal with the trauma they have but don’t know where it’s coming from,” he explained. Another reason could be children who are misinformed by their parents, who come from perpetrators’ families.”

He went on to say that the children of Genocide perpetrators who passed through this Mvura Nkuvure and learned the truth must also deal with the shame they feel.

He claims that Mvura Nkuvure contributes to the creation of a space where these young people can discuss their various experiences.

“We help these young people take the first step and understand what happened through their parents,” he said. “They can then heal and feel at peace.”

They are all in agreement that history is the best tool for breaking the cycle of intergenerational trauma.